From traveling the state in his occupation, Broadwater became well acquainted with army personnel. He also became acquainted with Amherst H. Wilder, a St. Paul entrepreneur who had contracts with the military. When Fort Assinniboine and Fort Mag-

innis were established in the 1870’s, Broadwater, through the association of Wilder, was able to secure the contracts for furnishing all of the construction materials for Fort Assinniboine as well as the contract for running the trading posts at both forts. Broadwater lived and worked at Fort Assinniboine near Havre and his nephew, Thomas A. Marlow, was one of the post traders at Fort Maginnis near Lewistown.

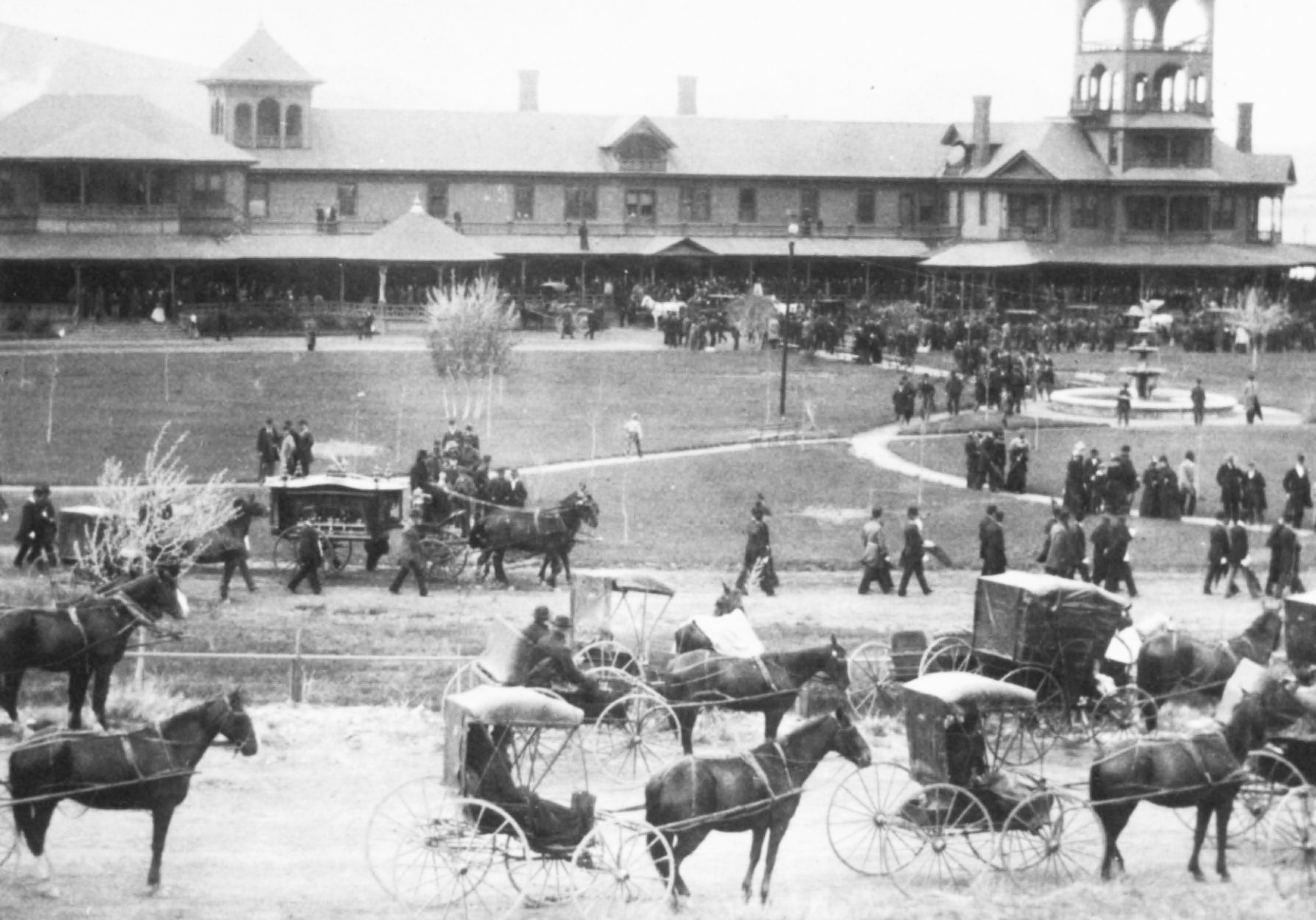

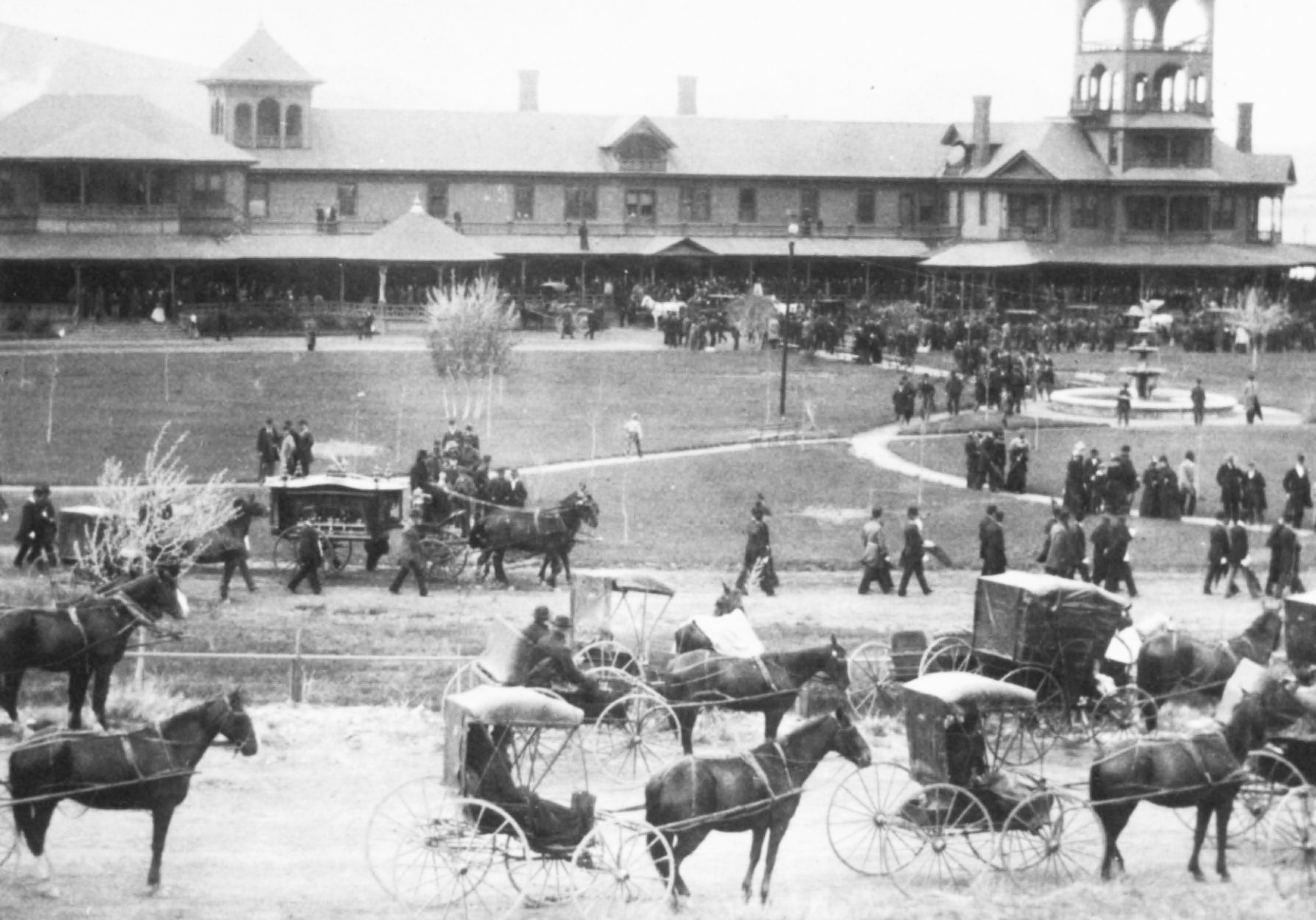

On May 29, 1892, over five thousand people gathered at the Broadwater Springs Hotel to attend Broadwater’s funeral, one of the largest ever held in Montana. Photo provided by MHS Photograph Archives

When railroads came in and forced freight businesses using oxen and mules out of business, Broadwater turned to other sources of income. A spur line needed to be built from the mines in Butte to the mills run by water power in Great Falls. Railroad magnet, James J Hill, recruited Broadwater, whom he met through Wilder, to be president in charge of building and operating the Montana Central Railroad, a job he did with skill.

While he was doing that, he also invested in a silver mine in Neihart; became the first president and a major investor of the Great Falls Water-Power and Townsite Company; was named president of the Great Falls’ First Na- tional Bank, and also was president of theSandCouleeCoalCompany. He started Montana National Bank in Hel- ena with financial backing of Wilder. With this wealth and friends through- out the state, Broadwater was consid- ered one of the state’s Democratic Party big four, along with Marcus Daly, Sam Hauser, and William Clark.

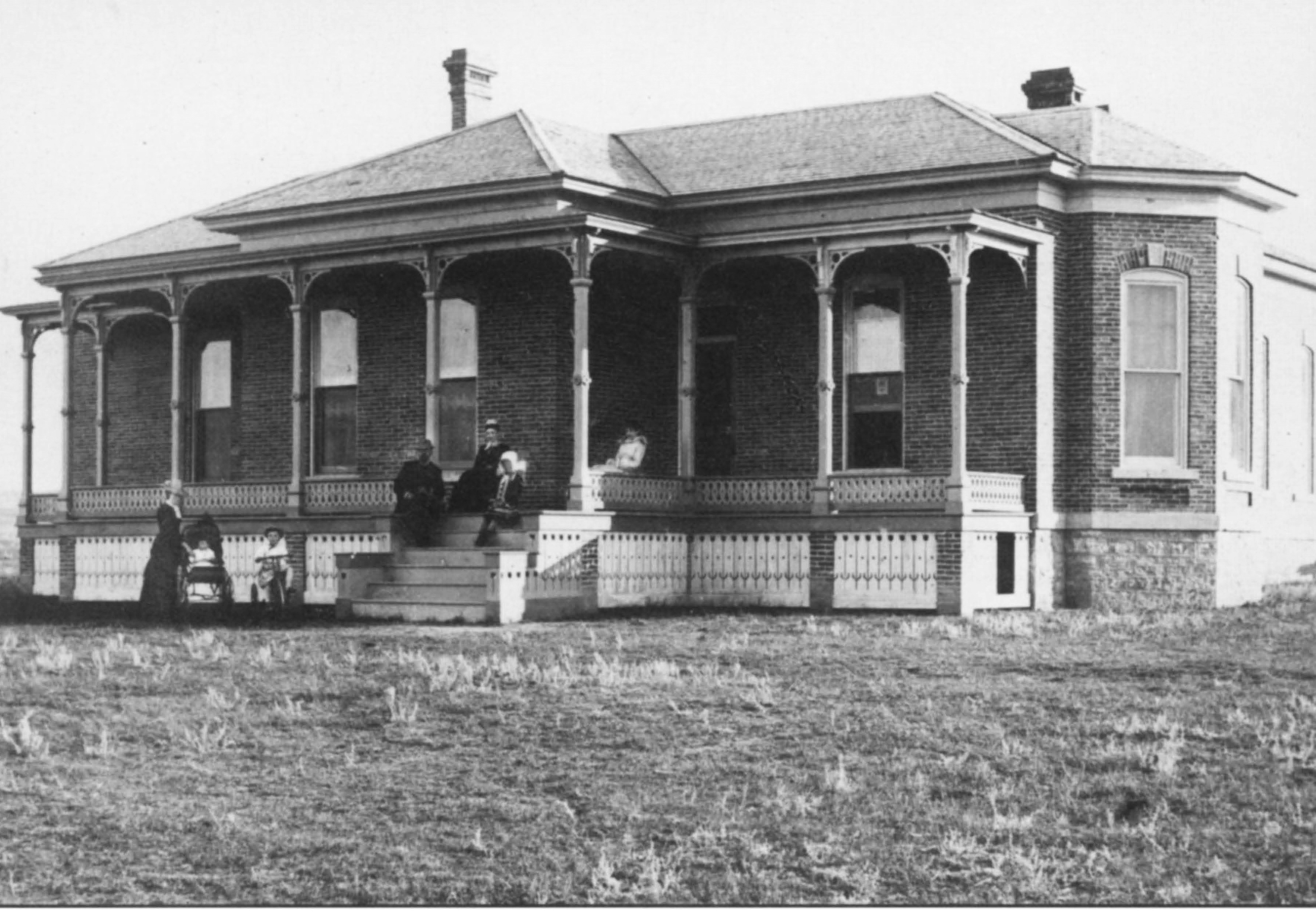

In 1873, Broadwater married Julie Chumasero, whose father was a Helena judge and a strong Republican, in a lavish wedding . Those giving gifts were the “Who’s Who” in Montana at the time. They lived at Fort Assinniboine, but later made a permanent home in Helena. They had two children, Charles C. Broadwater and Antoniette Wilder Broadwater.

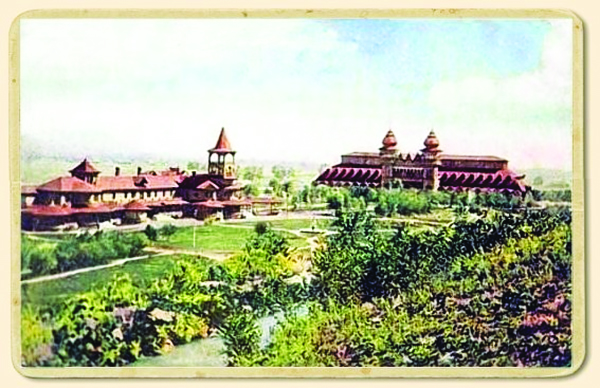

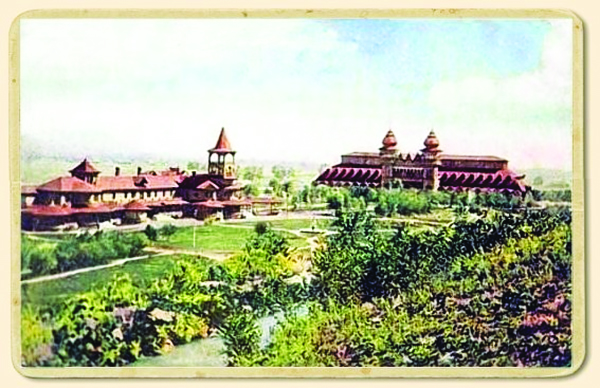

Broadwater will be most remembered for his foray into the tourist industry. He held eighty acres of land to the west of Helena that had both hot and cold water springs. In the late 1880’s he took on building a lavish resort hotel and natatorium that became the largest indoor swimming pool in the world. At one end of the pool were two waterfalls, one from the cold springs and one from the hot springs. Lighted by electricity, at night the natatorium “glistened like a jewel box.” Broadwater thought well-heeled clientele would come from throughout the country on the railroads. They would visit Glacier and Yellowstone Parks and stop at the hotel enroute. But the hotel was too isolated, and the resort gradually fell to disuse.

Although only fifty-two years of age, Broadwater’s body grew tired from all of the energy he had expended over the years. His doctors told him that he had a smoker’s heart. He tried an overseas trip and then a stay on the east coast, only to contract influenza. Upon returning home, he died in Helena on May 24, 1892. To transport the five thousand people who attended his memorial service, additional trains from Butte, Billings, and Great Falls were scheduled.

At Broadwater’s untimely death, many of his projects were unfinished and needed someone with energy and busi- ness sense to continue them to fruition. Broadwater’s nephew, Marlow, took on the job and was fairly successful.

Postcard of the Broadwater Hotel and Swimming Pool Building. Courtesy of History Museum

Only with the name of the county of which Townsend is the county seat is C. A. Broadwater remembered today. Gone is the Neihart mine where over two million dollars of silver was extracted. Torn down is the lavish Helena hotel and natatorium. But the people of Great Falls celebrate his interest and investment in a new community—one that he thought had a bright future.

It is unlikely Broadwater Bay in Great Falls was named for the early pioneer, C. A. Broadwater.

Even

before a board that named the parks was created, the term, Broadwater Bay, was being used in newspaper articles in the 1880s to identify the quiet, wide expanse of the Missouri River located west of downtown.

By 1894 the mayor and the newly formed Park Board Commission had started looking for tracts of land that would become parks. A designated piece of property identified as Sun River Tracts and, at that time, located outside the city limits was sold to the city in

two parcels by David Thomas and James Chambers in 1890 and 1894 respectively. Becoming one parcel of land, it had extensive frontage on the Sun River.

This area was to be named Broadwater Park to honor C. A. Broadwater, “Montana’s most illustrious citizen and a warm friend and believer in the destiny of Great Falls.”

When these Sun River Tracts were later officially named, it became Wadsworth Park in honor of O. F. Wadsworth, one of the park commissioners. Because the Park and Recreation Department records indicate that Broadwater Bay Park was named in honor of C. A. Broadwater, it is entirely possible that the honor was later officially transferred when the Broadwater Bay area became a park .