Battling the Elements for One’s Very Existence on Montana’s Plains

Text and Photography by Mahlon Kriebel

Town of Floweree. View is south to Little Belt Mountains. Pioneer town is cluster of gray buildings in middle of photo.

Great Uncle Clarence in front of Grandfather’s shack in 1937.

The Montana Prairie was open cattle range until the 1890s when the government surveyed the prairie into 36 square mile townships with each square mile divided into quarter section homesteads. Grandfather was born in Oklahoma Territory in a ‘soddy’ of prairie turf, dirt floors, and a planked roof. He was hardened to rough living. My great-grandfather “ran” in the 1889 Oklahoma land rush, and family stories of those times are every bit as exciting as portrayed in movies and novels.

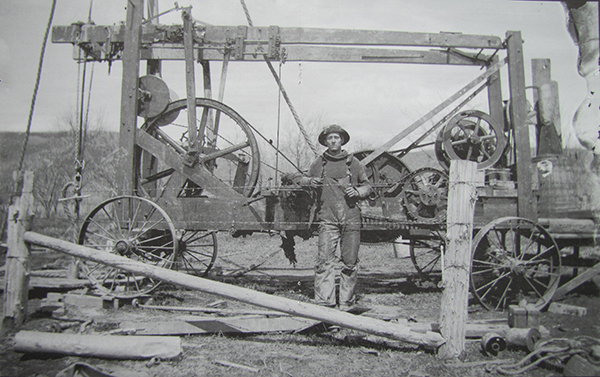

Granddad with his well-drilling rig mounted onto wagon.

After two days, my grandparents’ boxcars were uncoupled at Floweree, Montana. They drove their buckboard to Carter which had a land patent office, where ‘Locators’ working for the Northern Pacific Railroad Company promised “free” farms where “you can work for yourself, work all the time and give your children a head start”. Their promise of ‘work’ was the only truth in their guidance. Granddad’s homestead patent was number 22,000. Few sodbusters had cash to pay the usual $4.00 an acre to “break-out” the buffalo grass sod with a 16-mule team or a steam-powered tractor.

View into kitchen. Jumble of joist, rafters and plaster lathe. Small patch of red plaster clinging to far wall.

North of Floweree stands a derelict house in an enormous field. When walking to the ruin I startled a herd of antelope. Sensing no threat, they stopped, looked back, then drifted over the horizon. Grandfather claimed pronghorns know if a person carries a rifle.

A windrow of field stones guards the old house of vertically sawn red fir, now scoured of paint. Sections of foundation have collapsed leaving the floor to molder. Roof and ceilings have fallen into a jumble of plaster lathe, joist and rafters. The six-panel vertical fir doors, wainscoting, chair rails, and picture moldings indicate a one-time fine home.

As I daydreamed: “Had my grandmother sipped tea in the parlor?” A voice bellowed from a man on an ATV: “Hey, what the hell you doin’ in there?”

Gaining a modicum of composure I managed: “Just lookin’ ‘round.”

“You’re trespassing, is that your car?”

Then I noticed his rifle: “Yes!”

“I was hunting coyotes. Thought you broke down.” grunted the farmer.

I responded: “I’d thought this was a homestead.”

A smile broke his weathered face: “Well, this weren’t no shack! Where’re you headin’?”

“To my granddad’s homestead.”

The farmer nodded: “Only hunters stop to hunt antelope. See the rock piles?”

“Yes”

“Well, there is a story, wanna hear?“

“Of course.”

The farmer swung a leg over the saddle: “In 1880, a St. Louis deck hand reached Fort Benton only to find no work so he walked towards Great Falls. It was late when the drifter reached a ranch house. He knocked. An old rancher answered. The two men, separated by two generations, stood awkwardly. The drifter managed: ‘I need work?’”

The farmer, rolled a cigarette, pointed to the rock pile: “The old rancher said he could clear rocks from the yard.” The farmer savored his smoke: “The drifter pitched rocks for two weeks. Then asked ‘what’s next?’ The rancher replied: ‘Well, toss the rocks back’. The young man didn’t hesitate to scatter the rocks. The rancher exclaimed: ‘You’re the first drifter to throw ‘em back. Why?’ The drifter didn’t look up: ‘Well sir, you pay $2.00 a day, cook good food and the tack room is warm.’ “

The farmer’s eyes misted: “The young man stayed on. The old rancher died! The drifter rolled him in a cow hide and buried him. A winter passed. A lawyer from Fort Benton found the drifter fixin’ fence. The rancher left the ranch and cattle to the drifter. My granddad.”

The farmer cleared his throat: “Granddad built this house. When Dad moved to town, he couldn’t tear it down. Neither could I.”

We savored the moment. “That’s a good story. I know who drilled the well.”

Surprised the Farmer replied: “Who?”

Looking at the well pump I began: “Most grand homes were built over the well so the pump was in the kitchen.”

I paced five steps to the water pump: “this concrete cover is fifteen feet from the kitchen. My Granddad witched to find water and always found it 15 feet from the kitchen! I bet my Granddad drilled this well one hundred years ago.”

Shaking his head, the Farmer replied: “Dad said a fellow by the name of ‘Jigs’ drilled it. Jigs danced while playing the fiddle at hoedowns.”

Laughing: “That’s my granddad. I wondered how he got the moniker Jigs”.

“I’m sorry to tell you that I burned Jig’s shack twenty years ago. By the way, his wells were always alkaline”. The farmer chuckled: “But most wells are alkaline”.

I rode behind the farmer to the car. With his directions, Moni and I drove to “Jig’s” homestead. We couldn’t appreciate homesteader life in a car with AC, a GPS, snacks and beer. With wagon, my grandparents needed two hours to reach their homestead and we made the intersection of West Floweree and Starr Roads in minutes. Half mile south on Starr Road was Jigs homestead guarded by rock piles. Homesteaders used 40 acres for pasture, 40 for hay and seeded the remaining to wheat and oats. With a team of horses a sodbuster needed twenty seven days to turn 80 acres. He probably wore out his boots because he walked nine hundred miles behind a single bottom plow called a “foot burner”. Moni and I walked to where Jig’s shack had stood and picked up a couple pottery shards. Contrary to the promise of “Free Land” printed in Great Northern Railroad flyers, the land was not free. After registering in the patent office, the homesteader had five years to “prove-up” by building a house and planting crops. Then he could purchase the 160 acre homestead for $2.50 an acre. Sounds cheap but $400.00 one hundred years ago is equivalent to $10,000.00 today. Granddad didn’t have the cash to “prove-up” so he walked away. A few stayed and as farming techniques improved they managed to scratch a living.

The modern producer drives an air conditioned 550 horsepower tractor capable of pulling a fifteen bottom plow at seven miles per hour to cover 160 acres a day. Tractors are equipped with a GPS, a computer and automatic pilot to precisely control seeding, fertilizer, herbicide or pesticide applications.

Our journey had been successful. We visited my great cousin in Great Falls, walked where my father had played as a two year old and inspected the town of Floweree. I visited with a grandson of my granddad’s neighbor. As we drove to Great Falls with the moon on the horizon, bright as a newly minted nickel, I thought that Granddad Jigs had witnessed the change from horses and buggies to a moon landing.